In Israel, the defense industry is more than a business. Companies like Rafael Advanced Defense Systems, Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI), and Elbit Systems craft the tools meant to keep a nation safe: the Iron Dome missile defense system – which has become a perverse source of national pride, drones scanning hostile borders, and AI-driven systems guiding military precision.

These firms are the State of Israel’s crown jewels, global innovators born from necessity. Yet, their success, fueled by billions in taxpayer money, weaves a tangled tale of profit and power pulverizing public trust. As these giants post record earnings amid war, a question lingers: Are they protecting the nation, or cashing in on its suffering?

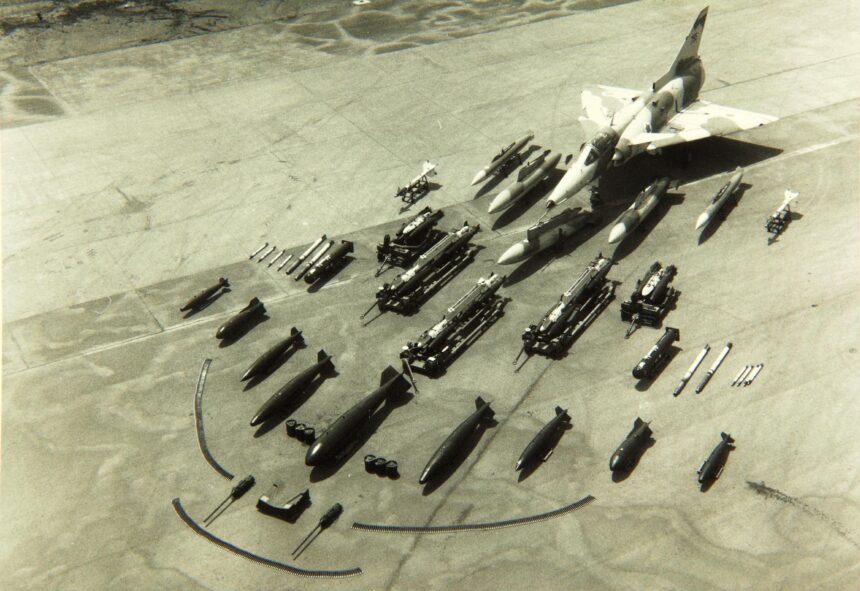

A Taxpayer-Funded Arsenal

Israel’s defense sector is a high-tech fortress, anchored by three juggernauts. Rafael, wholly owned by the state, started as a scrappy R&D lab in 1948, evolving into the maker of Iron Dome, a system that has allowed Rafael to capitalize on global geopolitical instability and the escalating need for air defense solutions. IAI, founded in 1953 to fix aircraft, now builds everything from satellites to the Arrow missile defense system. Elbit Systems, a publicly traded powerhouse listed on NASDAQ, grew from a Defense Ministry unit into a global supplier of drones, surveillance tech, and smart munitions. These companies don’t just arm Israel—they employ thousands and drive exports that rival the GDP of small nations.

The fuel for this machine? Israeli taxpayers. With one of the world’s highest per-capita defense budgets, citizens pour billions into contracts that keep these firms humming. In 2024, Rafael’s sales hit $4.8 billion—enough to buy every family in Tel Aviv a new electric car. IAI raked in $6.11 billion, a sum that could rebuild Jerusalem’s entire public transit system. Elbit topped $6.83 billion, equivalent to funding free university tuition for every Israeli student for a year. For state-owned Rafael and IAI, profits are supposed to flow back to the public via dividends—Rafael has returned $680 million since 2002, and IAI recently pledged $430 million from 2017–2023 earnings. But this cycle raises a prickly question: If taxpayers are the backbone, shouldn’t they expect clarity on where their money goes?

War’s Golden Harvest

Conflict is a constant reality for Israelis, and for defense firms, it’s a gold rush. In 2024, a year of intense military operations, Rafael’s profits skyrocketed 64% to $257 million—imagine buying a fleet of 2,500 armored ambulances. IAI’s net income surged 55% to $493 million, enough to build 10 state-of-the-art hospitals. Elbit, feeding heavily on Israeli contracts, saw 2024 revenues climb 14%, with its first-quarter 2025 sales jumping 22%, over a third from Israel alone. That’s like selling enough gear to equip every soldier in the IDF with cutting-edge tech, twice over.

These windfalls reflect the firms’ ability to meet wartime demand, but they also stir unease. Are these profits the fruit of innovation, or are companies hiking prices when the nation’s back is against the wall? For Rafael and IAI, the state is both boss and buyer, creating a highly inappropriate dance. If they charge inflated rates during a crisis, taxpayers overpay, only to get a sliver back as dividends. Picture buying a $100 emergency kit during a storm, only to receive a $50 “rebate” from the seller—who happens to be your own government. For Elbit, the stakes differ: its profits go to private shareholders, many abroad. In Q1 2025, Elbit paid a $0.60-per-share dividend, meaning a single investor with 10,000 shares pocketed $6,000—money traced back to Israeli taxes. That’s a new laptop for one shareholder, funded by citizens bracing for the next siren.

The term “war profiteering” casts a shadow, but Israel lacks a clear law to define it. Unlike rules curbing price gouging on essentials like bread or fuel during emergencies, no statute explicitly targets defense firms for excessive wartime profits. A recent government proposal to limit crisis-driven price hikes hints at public frustration, but without transparent pricing data—often hidden behind “national security”—it’s hard to know if taxpayers are getting a fair deal or footing an inflated bill.

Cracks in the Fortress

If soaring profits raise eyebrows, shaky governance fuels distrust. A 2023 State Comptroller report on Rafael exposed a wobbly foundation: its board, meant to oversee billions, had just four directors—imagine a major hospital run by a skeleton crew of doctors. The same accountant audited Rafael for 15 years, defying rules meant to ensure fresh eyes, like letting a single chef taste-test a restaurant’s menu for a decade. Dividend decisions, meant to return profits to the public, were sloppy, with the oversight body failing to enforce proper processes. These are not just paperwork problems—they are cracks that could let mismanagement or influence seep in.

The government’s triple role as owner, customer, and regulator of Rafael and IAI creates a tightrope. When ministers drag their feet on appointing board members, as the Comptroller noted, it smells of neglect or nepotism. Then there is the “revolving door”: officials who regulate defense firms today tend to sit on their boards tomorrow. Israel’s strict conflict-of-interest laws are supposed to keep this in check, but the risk persists, like a referee eyeing a future job with one of the teams.

Recent allegations, reported by Maariv and the Jerusalem Post, toss another grenade into the mix. Claims suggest Rafael, IAI, and Elbit signed deals with Qatar—worth tens to hundreds of millions—greenlit by the Defense Ministry and Prime Minister, begging the questions: Why sell high-tech arms to Hamas’ patron? Do these profits truly serve Israel, or do they subvert its security? For taxpayers, it’s like learning your mortgage payment funded a neighbor’s shady business venture.

AI Dangers

The industry’s leap into AI-driven warfare adds a new layer. Rafael, IAI, and Elbit develop systems like the IDF’s “Lavender” or “Gospel,” algorithms that guide targeting with cold efficiency.

But if machines decide who is in the crosshairs, who answers for mistakes? With 66% of IAI’s 2024 sales and half of Rafael’s coming from exports, the push for cutting-edge tech is as much about global markets as local defense. This risks “ethical fading,” where profit and innovation outpace moral scrutiny, potentially clashing with international laws demanding human accountability in war.

For a country that dubiously prides itself on moral clarity, this is a quagmire of its own.

Rebuilding Trust

Israel’s defense firms must be accountable. The State Comptroller, a state watchdog, needs sharper claws—authority to ensure its findings, like Rafael’s board woes, spark real change, not just reports gathering dust. Independent audits of big contracts should confirm taxpayers are not overpaying, like checking the receipt after a pricey dinner. A defense procurement ombudsman should give citizens a voice, a hotline for concerns about waste or profiteering.

Legally, taxpayers face steep climbs. Class-action lawsuits against defense giants are possible but tricky—proving personal harm from overpriced contracts is like pinning down a cloud. Petitions to Israel’s High Court could challenge government lapses, but courts often defer to “security” arguments. International courts, like the ICC, are irrelevant for these domestic financial disputes. The real fix lies in prevention: laws defining “excessive” wartime profits, transparent budgets, and boards staffed with independent experts, not political pawns.

Israel’s defense industry depends on trust. By tightening oversight, opening the books, and ensuring profits do not exploit crises, Israel can clear its conscience and sharpen its edge. For a people who live in constant crisis, that is a return on their investment they deserve.