The world might be described as a complex of interwoven interests, alliances, and conflicts. To more effectively comprehend the intricate interplay between nations, it is imperative to shift our understanding of geopolitics from a simplistic game of checkers to the nuanced and strategic world of chess, with a pinch of poker added in the equation.

In checkers, pieces move in a predictable, linear fashion, and the goal is straightforward: capture all opposing pieces. Chess, on the other hand, demands foresight, strategic planning, and an understanding of the multifaceted nature of each piece and its potential impact on the overall game.

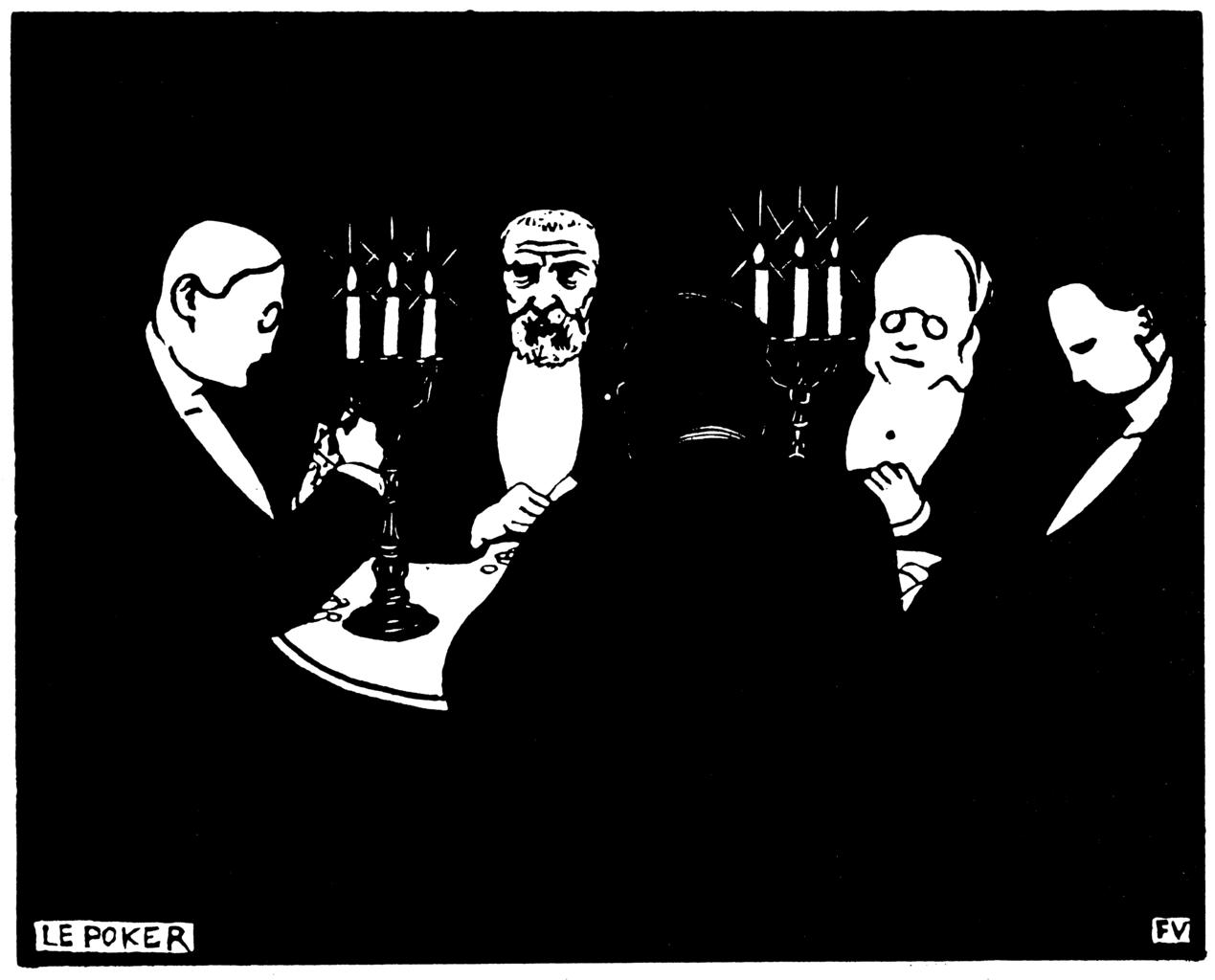

While the analogy of chess offers valuable insights into the strategic thinking and long-term planning involved, it alone falls short of capturing the full spectrum of geopolitical interaction. We must add another layer of complexity: the element of poker. Geopolitics is not just about strategic moves and calculated consequences, it’s also about bluffing, reading opponents’ intentions, and managing risk in an environment of incomplete information and outright information warfare.

Similarly, geopolitics requires a deep understanding of history, culture, economics, and military might, as well as the ability to anticipate the long-term consequences of actions and decisions. However, unlike chess, where all pieces are visible and moves are transparent, geopolitics is shrouded in uncertainty. This is where poker is analogous. Nations often operate with limited information, must make decisions based on incomplete data, and must constantly assess the credibility of their adversaries’ pronouncements.

In a 1975 speech at a luncheon in the CIA executive dining room by U.S. Ambassador to Ghana Shirley Temple Black, she explained: “The Soviets’ national sport is chess and their foreign policy reflects an effort at long-range planning of coordinated, integrated moves, although they often play the game badly and are given to serious blunders.

“The Chinese are notorious for planning their foreign policy carefully, with moves designed to reach fruition even years beyond the lifetimes of present leaders.

“By contrast,” Ambassador Black observed, “the United States is a poker player. It looks the world over, picks up whatever cards it is dealt, until the hand is won or lost. Then, after a drag on the cigarette and another sip of whiskey, it looks around for the next hand to be played.” (Former CIA Angolan Task Force Chief John Stockwell, In Search of Enemies, a CIA Story, 1978, pp. 174-5)

In general, Western nations, with their long histories of colonialism, imperialism, and power struggles, have often played the geopolitical game with a chess-like mentality. The rise and fall of empires, the intricate alliances forged during the Cold War, and the ongoing competition for resources and influence all reflect a strategic, long-term approach to international relations. For example, the United States’ involvement in the Middle East, with its complex web of alliances and interventions, can be seen as a calculated move to secure its interests in the region, more like a chess player maneuvering pieces to control key squares on the board.

China, with its rich history and burgeoning economic power, has also demonstrated a keen understanding of geopolitical chess. Its Belt and Road Initiative, a massive infrastructure project spanning Asia and beyond, is a strategic move to expand its influence and secure access to resources, echoing the strategic expansion of a chess player’s territory on the board. China’s approach to international relations is characterized by long-term vision and a patient, calculated approach, much like a chess grandmaster planning his moves several steps ahead.

The world of Islam, with its diverse cultures and complex internal dynamics, presents a unique challenge in the geopolitical game. The rise of extremist groups, the ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, and the struggle for power and influence within the Muslim world can be seen as a complex chess match, with various players vying for control and dominance. Understanding the historical grievances, religious fervor, and socio-economic factors that fuel these conflicts is crucial to comprehending the moves and countermoves in this intricate game.

The world is moving towards a tri-polar structure, not unlike the superstates in Nineteen Eighty-Four. This framework is essential for understanding the complexities of international relations, particularly in the Middle East.

A simple checkers analogy for geopolitics is insufficient because today, it’s not just nation-states; there are blocs (NATO), ideological movements (Sunni Islam), and even wildcards like Russia with its own distinct interests. Each of these actors has internal complexities and often conflicting motivations. A checkers game assumes simple, unified goals for each player, which is clearly not the case in geopolitics. For example, NATO, while presented as a unified bloc, contains individual nations with their own agendas and internal political dynamics. Similarly, the Islamic bloc is far from monolithic, encompassing incompatible interpretations of Islam and conflicting national interests.

Checkers is about capturing all the opponent’s pieces. Geopolitics is rarely about complete victory or defeat. It is more about managing power, influence, and resources in a constantly shifting landscape. The Cold War was not about one side definitively winning, but about a complex balance of power and deterrence. Even in conflicts, the goals are often limited – securing territory, influencing policy, etc. – rather than total annihilation of the opponent. The situation in the Middle East illustrates this perfectly. NATO’s interests, for instance, involve a complex balancing act: supporting Israel while not alienating Arab allies, countering Iranian influence while bolstering Saudi interests. These are not simple “win” conditions like in checkers.

There is also the fraud aspect of power. Geopolitics is a game of incomplete information, where actors often engage in deception, propaganda, and disinformation to advance their interests. Like poker, nations bluff, conceal their true intentions, and try to read their opponents’ tells. This element of deception is completely absent from checkers. Think of China’s approach, downplaying ambitions while strategically expanding its influence. This is a calculated move, a poker-like tactic, not a simple checkers move.

Chess, unlike checkers, requires thinking several moves ahead. Geopolitics also demands this long-term perspective. Actions taken today have ripple effects until the end of time. It’s not just about immediate economic gains for China; it’s a long-term strategic move to reshape global trade routes and increase Chinese influence. This kind of strategic depth is beyond the scope of a checkers game.

The geopolitical landscape is constantly changing. New actors emerge, alliances shift, and power dynamics evolve. A checkers board is static; the game pieces and their movements are fixed. In contrast, geopolitics is fluid and unpredictable. The rise of China, the fragmentation of the Middle East, and the resurgence of Russia all demonstrate this dynamic nature.

The thesis that geopolitics is best understood as a complex game of chess with elements of poker, rather than a simple game of checkers, has profound implications for how we interpret media reportage of the news. If international relations were truly as straightforward as checkers, media coverage could focus on reporting observable moves and their immediate consequences. However, the reality is far more intricate, demanding a critical and discerning approach to news consumption.

Just as chess players strategize several moves in advance, and poker players bluff and misdirect, nations engage in calculated actions with long-term goals that are often obscured from public view. Media reporting frequently focuses on surface level events – a summit meeting, a policy announcement, a military deployment. However, these events are often just pawns in a larger game. The real story may lie in the unspoken agreements, the behind-the-scenes negotiations, and the long-term strategic objectives.

In a world of competing power blocs, information is a weapon, pointed at YOU. Just as poker players try to control the narrative at the table, nations engage in information warfare, spreading propaganda and disinformation to influence public opinion and advance their interests.

Media outlets are conduits for this propaganda. A chess/poker mindset encourages us to question the source of information, identify interest-driven bias, and look for corroborating evidence before accepting a news report at face value.

Media reporting, by its very nature, deals with the observable, the tangible. However, this can create a misleading picture of clarity in a world of inherent and deliberate ambiguity. News consumers must recognize that what is not being reported can be just as important as what is. The chess/poker analogy reminds us that there are always hidden cards, unseen moves, and unspoken motivations that can significantly impact the course of events. For example, media reporting on diplomatic negotiations often focuses on the public statements of the participants. However, the real bargaining may be happening behind closed doors, the public pronouncements mere posturing.

A checkers game can be understood in isolation. Each move has a direct and immediate consequence. Geopolitics, however, is deeply rooted in history, culture, and ideology. Events cannot be understood in isolation; they must be placed within a broader context. Understanding the ideological competition between different power blocs is crucial for interpreting media reports.

News consumers should ask themselves: Who are the actors involved? What are their motivations? What are the potential long-term consequences of this event? What information is missing? By adopting a chess/poker mindset, we can become more discerning consumers of news, better equipped to make important life decisions.